Lifelong Learning - Need and Funding was the subject for the hearing of the German Parliament Committee for Education, Research and the Implications of Technologies on 29 January 2007 in Berlin. In the following we reprint the report given by the German Adult Education Association (DVV) for this hearing.

1. How do you assess the current and the mid- and long-term need in Germany for continuing education and training, and for lifelong learning?1

General and vocational continuing education is gaining in importance in the context of Lifelong Learning. Whether guaranteeing a (skilled) potential labour force and employability in the wake of demographic change, the individual's ability to play a part in democracy, integrating citizens from a migrant background, guidance on values in our society, or preventative health care, ageing and pension provision, the ability to meet these challenges is dependent on the level of education, degree of knowledge and ability to make judgments and take action of the population. In Germany in particular, a well-educated, enlightened and productive population provides the crucial potential for economic growth and participation in society.

2. How do you assess the need and practicability of further expansion of the continuing education sector into a 4th pillar of the education system?

Continuing education after completion of initial education accounts for the longest stage of Lifelong Learning, and is therefore addressed to the largest segment of the population. As the Committee of Experts on Funding Lifelong Learning pointed out, continuing education is of distinct and growing importance since it constantly opens up new occupational and social opportunities at a time of permanent structural change. Given its increasing importance and the growing need for it, the state is requested to guarantee basic national provision of general, political, cultural and vocational continuing education in the public domain and to develop continuing education into a recognised and equal fourth pillar of the education system.

In the context of the necessary overall expansion of continuing education, we regard the following areas as having a particularly urgent need for continuing education.

Improving the involvement of migrants and of excluded people of German origin in politics, society, social systems, the media, etc., is one of the greatest challenges facing the education system, against the background of demographic changes - and it must become a focal point of the entire debate on education policy. Given the urgency, the DVV calls for the development of a "second chance" programme.

3. How do you view the connection between continuing education and/or lifelong learning and longer working lives?

There has to be a radical change of awareness in vocational continuing education and training, so that continuing education and training activities are taken seriously as essential, legitimate phases of working life and as a natural task for enterprises and employers.

An intelligent balance needs to be achieved between training, study, family breaks and continuing education. Phases of unemployment need to be used for training for active life.

Updating training needs to focus more strongly on problem groups, the low-skilled and those with no training, and on older workers. Older workers, who are likely to increase in numbers as a result of the raising of the retirement age to 67, and may amount to between 1.2 and 3 million people (Rürup 2006), can only remain successfully integrated into working life through regular participation in vocational continuing education and training. By comparison with other European countries, Germany lags behind in respect of participation by older workers in vocational education and training.

It is not only vocationally oriented education which has an impact on the economy. There is also a need in Germany for additional general and political education, which will ensure future social stability as well as producing an economic return. This means, for example:

political education, which can ensure the ability to play a part in democracy and society, in the context of growing antidemocratic trends,

family education, which can strengthen parents' responsibility for bringing up children and teaching values, in the context of increasing disorientation among children and young people,

intercultural education, in a society in which many cultures are living side by side,

health education, which can encourage people to take responsibility for their own health and prevention in the context of spiralling health costs,

financial education, which reveals complex interconnections and motivates people to look after themselves, in the context of regressive demands on state welfare (e.g. pensions),

4. How do you view the connection between continuing education and changes to the pattern of working lives (including periods of unemployment)?

personal development education, in order to take account of changes in working lives, tools such as skills profiles, modularization of training and counselling, and support structures, are becoming increasingly important. In patchwork lives, a solid basic store of soft skills and "learning to learn" skills is also needed. It is well known that the latter are particularly poorly developed in educationally disadvantaged target groups.

Both among policy-makers at EU, national, Land and regional level, and among social groupings, increasing emphasis has been placed in recent years on the need for Lifelong Learning, and particularly for continuing education and training.

5. What in your view is the present status of participation in continuing education and training in Germany? How do you evaluate this participation in comparison with other countries?

Paradoxically, participation in continuing education has been falling in Germany over the same period. While 48% of adults took part at least once a year in continuing education in 1997, the proportion was only 41 % in 2003. The decline equally affects general (1997: 31 %; 2003: 26%), vocational (1997: 30%; 2003: 26%) and workplace continuing education (in decline since 2000). The argument frequently put forward among politicians, that people are increasingly learning informally rather than in an organized forum, is not true, since participation is also falling in informal learning.

Until 2002, the Volkshochschulen were still showing a rise in enrolments. This was no doubt positively affected by improved delivery and quality assurance, greater attention to student counselling, expansion of modular systems in languages and computing, and demand-driven growth in preventative health education. The four decades of continual growth in participation seem now to have stopped, however, falling from a high in 2002 to a level 5.8% lower in 2005.

There is much to suggest that the decline in participation in continuing education stands in a causal relationship to the reduction in public support: in European countries where the state makes more resources available for Lifelong Learning (e.g. the United Kingdom and the Scandinavian countries), take-up of continuing education and training is continuing to rise. Participation in continuing education in Germany is well below the European average.

6. What is the make-up of participants in continuing education and training, and what groups are in your view under- and over-represented? What do you think are the likely reasons?

In line with the trend in the whole field of continuing education, a good level of formal education and vocational qualifications in-crease the likelihood of participation in the Volkshochschulen. That does not mean that educationally disadvantaged groups cannot be won over and motivated to take part in general continuing education. In numerous projects in such areas as literacy, basic education and second-chance school-leaving qualifications, and in political education, promising and effective strategies and practices have been developed, such as educational pick-up counselling, integrative educational social work, and links between work and general education. In the area of second chance education, many Volkshochschulen have a well-developed array of adult education tools. Since these measures are very cost-intensive and little or no fees are charged, this work is heavily dependent on public support. The constant growth of short-term project funding in this area is leading to considerable friction.

Participation by non-German students in continuing education has remained relatively stable in Volkshochschulen. In the wake of the adoption of the Immigration Act, it is evident that even educationally disadvantaged target groups such as migrants can be reached where there is targeted state support.

7. Would it be sensible, in your opinion, to set targets for participation in continuing education and training in Germany?

While the Continuing Education Reporting System shows that those over 50 years of age take part appreciably less often in continuing education than younger people, an analysis of long-term changes in enrolments by age group demonstrates that the older working population in the Volkshochschulen has risen considerably in recent years by comparison with population changes. New types of age-appropriate learning are being used, and these will need to be further expanded in the coming years.

8. In your view, what are the most important target groups for continuing education and training? Do you anticipate medium and long-term changes?

In recent years, the Volkshochschulen have increasingly been taking on a continuing education role for people employed in small and medium-sized enterprises. A sustained growth in continuing education participation can only be achieved, however, by means of a varied set of counselling and support instruments (possibly after the model of North Rhine-Westphalia education cheques).

9. How do you assess the appropriateness and suitability of continuing education and training for the target group, and in relation to the need to combine continuing education and training, employment and family life, and how can these be improved?

The Volkshochschulen also recruit a disproportionate number of women, who account for more than 70% of students. Changes to the legal arrangements for parental leave are now making new demands on continuing education. While it was chiefly women who used to be offered special return to work courses after a family break, "parental support" provision now needs to be designed to update the potential and skills of those concerned so that they can keep in touch.

11. How do you view counselling, information and transparency in vocational continuing education and training?

Counselling, information and transparency of provision are often organized satisfactorily by individual providers. From the point of view of the citizen who would like an overview of the provision of the various local providers, however, the continuing education and training market tends to appear complex and confusing. It is apparent from the experience with education vouchers, for example, that inexperienced people find it difficult to judge the quality and appropriateness of the range of provision without help.

12. How do you assess the success of continuing education and training provision overall, especially its ability to meet economic, educational and social requirements effectively and efficiently?

13. What methods and approaches can be used to achieve and improve reliable monitoring of the success of provision?

Since citizens are expected to make their own realistic decisions about their educational careers, the continuing education system needs to have available a publicly sponsored counselling infrastructure guided by the needs of the regional market and the best development interests of the individual. A competent biographical approach is crucial, backed up by suitable instruments (educational passports and profiling). It would be beneficial to locate such an infrastructure in the Volkshochschulen, which are universally accessible and have the requisite expertise in counselling. The independence of the advice can be guaranteed by the fact that local authority providers require their establishments to be neutral, and external evaluators regularly check that the rules are being observed.

The checks on input factors traditionally available in the field of continuing education (curricula, training of course tutors, teaching materials, etc.) have been systematically expanded in recent years to include output checks. Courses increasingly end with a final test, a pass in which is documented with the appropriate certificate. This development is particularly marked in the case of languages courses (cf. the B1 examination at the end of the course for immigrants) and in the area of vocational continuing education. Courses are generally passed successfully. Failure rates significantly increase, however, where the number of course hours is inadequate (BAMF integration courses) or individual attention to problem groups has to be curtailed for lack of funds (e.g. educational social support for lower secondary school-leaving examination courses).

14. To what extent is there any ongoing quality assurance of continuing education and training provision in relation to reaching the target groups identified and to meeting economic, educational and social needs? What should be done in your view to improve quality assurance?

15. How could active educational marketing help to underpin lifelong learning, and how do you think this would need to be arranged?

Many continuing education providers - including the Volkshochschulen - have in recent years set up quality management systems. This is complicated, however, by a lack of coordination in the registration of sponsors and activities between the federal and Land governments, and among fund-awarding bodies. The consequence is that establishments that wish to work with a variety of state agencies are often obliged to seek multiple certification at additional cost in terms of money and time. Efforts to improve quality are also hindered by the practice of competitive tendering which - as in the case of vocational continuing education publicly sponsored by the Federal Employment Agency - forces providers into ruinous price competition.

16. How can (second chance) continuing education and training reach out to those who have no school-leaving qualifications or lack vocational training? What experience from other European countries with targeted second-chance programmes should be taken into account?

Sample surveys (e.g. by the Land Adult Education Associations of Bavaria, North Rhine-Westphalia, Lower Saxony, Saxony and Thuringia) demonstrate that course participants' level of satisfaction with Volkshochschule provision is extremely high. Studies also show that continuing education appreciably enhances chances of occupational advancement. However, the facilities available to providers do not allow them to extend these opportunities for everyone to succeed through continuing education to the whole of society. State support for continuing education analogous with other areas (e.g. top-up pensions) is urgently required if interest and participation in continuing education is to be increased. Any such campaign would need to be designed and coordinated nationally, but delivered locally.

The aim should be to demonstrate especially to poorly trained young people and young adults that one period of education in life is no longer enough to meet the challenges of the labour market. However, a marketing campaign can only be effective if adequate funds are made available.

17. How do you see the relationship between the responsibilities of private individuals, the public purse and business, to fund continuing education and training, both now and in the future?

The funding of continuing education in Germany is marred by two unfortunate developments. First, the Federal and Land Governments have been cutting back for years on their financial involvement, although it has been demonstrated, at least since publication in summer 2004 of the well-founded final report of the Committee of Experts on Funding, Lifelong Learning, that underinvestment in continuing education has a serious impact on the state, the economy and individuals. Secondly, as part of its restructuring of financial instruments, the state has relied one-sidedly on stimulating demand, while discontinuing its support for the structure and preservation of provision. The direct consequence of this unambitious continuing education policy is to place provision for all groups of the population at risk and to destroy well-established institutions.

Since 2002, public spending on continuing education in Germany has been below the level of 1995. As part of its new social policy, the Federal Employment Agency has reduced spending on support for vocational continuing education and training (course fees and maintenance payments) by over half (1996: 8 billion euros; 2004: 3.6 billion euros).

At the same time, Land contributions, which are particularly vital to the infrastructure, have fallen. While the Volkshochschulen received 156 billion euros from the Laender in 1995, the figure was only 132 billion euros in 2005. Up until 2003, declining contributions from Land governments were offset by local authorities. Since then, local government involvement has also stagnated. As a result, average course fees in Volkshochschulen for one hour of tuition rose by 48% between 1995 and 2005 (2005: 2.12 euros per hour; 1995:1.43 euros per hour).

Overall, it can be observed that increasing numbers of people are being excluded from significant continuing education and training development that could be of benefit for their occupational or personal advancement because they cannot afford the course fees. The victims of this development are precisely those educationally disadvantaged groups of the population who need special support, such as the long-term unemployed, older workers, those with low skills, migrants, school drop-outs and illiterates.

The effectiveness of state support is further impeded by a mismatch between the management of supply and demand. Course enrolments made possible through education vouchers issued by the Federal Employment Agency and BAMF are often not taken up on the demand side (BAMF vouchers issued in 2005: 215,651; course enrolments:115,158), while on the supply side there is a shortage of funds for courses of immediate public benefit. The DVV estimates, for example, that there are currently 10,000 young people wishing to take second chance school-leaving qualifications on the waiting lists of the Volkshochschulen. However, because of lack of funds from Land governments, these courses cannot be offered.

The DVV regards it as essential that after the investment in child care, schools and higher education, an investment programme for continuing education should now be introduced as well. This must contain four elements:

We estimate the financial requirement for the whole programme at around 3 billion euros over five years, some 2 billion of this being needed solely for the programme to combat educational disadvantage.

At the same time, businesses should be encouraged to make greater investments in the continuing education and training of their employees, since they benefit considerably from the skills of their workers.

19.What material support and promotion measures would in your opinion be advisable to make second chance initiatives and programmes more successful (postponed acquisition of school-leaving qualifications and vocational training)?

Lack of equal opportunities is the most serious and shaming flaw in the German education system. According to the data report of the Federal Office of Statistics, 1.85 million people had no school-leaving qualifications in March 2004, with around 85,000 young people being added each year. Up to 15% of 20 to 29-year-olds have never completed any vocational training. At the same time, functional illiteracy is estimated to affect in the order of four million people (Bundesverband Alphabetisierung) - a growing problem resulting from unsuccessful literacy teaching at school (just over 40% of functional illiterates have a school-leaving qualification according to estimates) or from loss of writing ability after leaving school.

Germany lags well behind other European countries in relation to the rate of success of those with low skill levels in the labour market. Current educational initiatives by the Federal Government in favour of illiterates and school drop-outs, the number of whom is to be halved over a period of five years, have come at the right time. If the school dropout generation of recent years is not to be written off permanently, complementary measures are also urgently needed, however, in order to expand a second chance programme in continuing education. In addition to research and development projects, funding and policies now need to be put in place to implement these in continuing education practice.

Among school drop-outs we can assume from the experience of the Volkshochschulen that interest in taking school-leaving examinations is largely restricted to 15 to 30-year-olds, who might account for around 500,000 people from an extrapolation of the 2004 microcensus figures. If half of them were to take a lower secondary school-leaving examination course (250,000), and if the average national cost is estimated at some 4,000 per student, that means a budget requirement of 1 billion euros for such courses. Living costs are not taken into account in that figure.

While there is a clear excess demand for school-leaving examination courses, it is far harder to recruit students for literacy courses because the majority wish to remain anonymous and there is of necessity no written advertising. This relies chiefly on "mouth to mouth propaganda". Against this background, the target of a reduction by half is scarcely attainable. It would be a huge success if another 250,000 people were to be taught literacy over the coming five years, by analogy with school-leaving courses. The costs are difficult to put a figure on because of the differences between courses (between 240 and 1800 hours), but let us estimate them also at around 1 billion euros.

20. What is your general view of the way in which an Adult Education Promotion Act might help to achieve and to provide funding for the aims of continuing education and training and of lifelong learning?

In a knowledge-based society with the demographic outlook of Germany, interest in and willingness to engage in continuing education and training must not be blocked by financial barriers in any group of the population. The philosophy of funding suggested by the Committee of Experts should be guided first by the principles of ability to achieve and to benefit, but there must also be a balanced relationship between tools used to stimulate demand and assurance of a balanced structure of provision. Lifelong Learning for All can only be delivered via a national system of provision delivered locally so as to stimulate educational need (for Volkshochschule courses) and to provide the population reliably with a full range of significant education products.

21. In particular, how do you assess the possible contribution of an expansion of a legal entitlement to continuing education and the creation of any additional elements that may be needed for success?

One particular goal should be for every adult - regardless of income - to be in a position to take school, higher education and vocational qualifications after the normal age. Since school drop-outs make less use of the state education system and therefore cost less than those completing higher education, for example, it would be equitable if the costs of second chance courses were covered by the state as a matter of course up to the end of upper secondary education and if learners or their families were given help with living costs in case of need.

Experience of implementing the Migration Act shows that legal entitlements to continuing education go hand in hand with a marked rise in supply and demand. This being so, Land laws providing for the funding of second chance education and training qualifications would send an important signal to the target groups concerned.

18. Against this background, how do you assess the present structure of state support for continuing education and training (SGB, AFBG, EStG, BaföG etc.) and the overall relationship between grants and loans?

At national level, the BaföG (the law on higher education grants) also needs to be adapted to the needs of continuing education and extended so that all adult learners are covered. It is impossible for people with low incomes and little capital to undertake lengthy periods of intensive learning without some guaranteed coverage of their living costs. The existing rules only apply to young adults, have gaps in regard to important target groups (e.g. the children of migrants) and place senseless bureaucratic obstacles in the way of the work of education providers. Courses leading to school-leaving examinations are, for example, regarded as not eligible for BaföG grants by regional governments if just one student fails to meet BaföG criteria.

In the interest of transparency, comprehensibility and fitness for purpose, it would be advisable legally to systematize the various funding instruments available to adult learners from national government and to bring these together in an Adult Education Promotion Act.

22. How do you assess generally the way in which new tools such as educational savings schemes, education grants and educational loans might help to achieve and fund the aims of continuing education and training and of lifelong learning? What population groups are addressed particularly by the three above-mentioned tools?

The Federal Government is currently focusing its thinking about continuing education funding on educational savings schemes, for which a proposed three-part model has been available since 10.01.2006 (continuing education grants, expanding the Formation of Wealth Act to include the possibility of saving for continuing education with an early cash withdrawal option, and continuing education loans), based on two expert reports (Rürup, Dohmen).

23. How do you assess the advantages and disadvantages of the various models of "educational savings scheme" being discussed, and their financial consequences for employees, business and the public purse?

This clear set of proposals demonstrates a change in awareness of the value of continuing education which is relevant and of a symbolic value that should not be underestimated. A continuing education option for the sums amassed under the Formation of Wealth Act would place investment in human capital on an equal footing with capital savings. A link with education grants (for up to 50% of continuing education fees) would mean that saving was given priority over consumer spending.

The main weakness of the proposal lies in the restriction of the measures eligible for support to vocational continuing education and training, and this cannot be justified in policy terms. Regardless of the universally recognised difficulty of distinguishing between private and vocational purposes, it demonstrates an antiquated perception of education which negates the social and occupational benefits of general continuing education.

24. What would be the likely impact and consequences of the introduction of an educational savings scheme for continuing education?

But even if general provision were to be covered by the support system, as is urgently required, the limited horizons of continuing education savings schemes cannot be overlooked - the authors estimate 3.5 million interested persons. Many of those in receipt of low and middle incomes on whom the focus should be are excluded from taking advantage of the schemes because they are unable to save, and they tend to belong to groups alienated from education. Furthermore, the moderate size of the amounts saved means that the activities funded would generally be short-term, while more costly measures, such as second chance school-leaving and vocational qualifications, would require other support tools (see above).

25. What measures do you regard as necessary and sensible in order to ensure adequate acceptance of an educational savings scheme by comparison with other provident schemes such as building society and pension savings schemes?

26. How do you view the possibility of restructuring and extending building society savings accounts as an appropriate system for funding continuing education and training and lifelong learning?

If the Federal Government keeps to the principle of budget neutrality, with the result that education grants become out of the question, educational savings schemes will not have any significant impact. Grants for a percentage of fees, on the other hand, can make an appreciable addition to the range of funding available for continuing education (AFBG, BaföG, SGB, fiscal options, Land and local authority support) and can mobilize those on low and middle incomes, and they should therefore be seen as a first step towards a new system of funding continuing education.

Ongoing, sustained planning of education and training based on the needs of employees and employers will in future be indispensable. As is shown in the new public service wage agreement (TVöD), which devotes a separate section (§ 5) to training for the first time, and other wage agreements, the parties to wage negotiations increasingly recognise the importance of training and planning as a part of systematic staff development. However, this welcome change is still short on implementation.

29. What is your general view of the ways in which wage or company agreements might help to achieve and provide funding for the aims of continuing education and training and/or lifelong learning? What supporting legislation is advisable and necessary?

Even at a casual glance, attractive support programmes may evaporate. One example of this is the national programme to and training costs for enterprises with up to 250 employees which employ workers over 45 years of age (50 years of age in the previous programme). The Federal Government itself complains of the lack of impact of this support scheme in its response to the 5th Ageing Report.

30. How do you view in particular existing or proposed wage agreements and settlements in relation to continuing education and training (long-term accounts, continuing education funds, learning time accounts, etc.)?

Given the weak impact of the instruments used to date, we would argue for an expansion of support for workplace continuing education and training. Continuing education funds should be introduced, as in France (see the final report of the Committee of Experts on Funding Lifelong Learning): all enterprises spending less than a prescribed percentage on continuing education and training would then have to pay into a fund administered equally by the social partners. Additionally, state money for specific target groups (e.g. older people, those with little or no training) could be paid into the fund.

31. How can and should long-term accounts be guaranteed in order to prevent loss of continuing education entitlements (in the case of insolvency, dismissal, change of employer, etc.)?

A fund solution offers two crucial advantages: first, it makes businesses invest, even in times of economic difficulty, when continuing education and training are particularly necessary but are often not funded because of cost pressures. Secondly, the sums paid into the fund are calculable and provide a set amount of funding for workplace continuing education and training, while experience tells us that continuing education and training support schemes laid down solely in wage agreements are implemented by employers in widely varying ways. In any case, ongoing support for continuing education and training which covers all employees in a sector cannot be achieved via wage agreements alone, especially as businesses not bound by those agreements are automatically excluded.

32. What additional tools or measures not explicitly mentioned here do you regard as advisable to meet the aims of continuing education and training, and/or to guarantee the funding required (e.g. job rotation)?

Learning time accounts, in the form of ring-fenced amounts of time for continuing education and training, are to be welcomed. They may have an even greater impact on the labour market if they are complemented by job rotation models (fixed-term employment of the unemployed as substitutes). The basic problem with long-term accounts lies, however, in the alternative ways in which they can be applied (i.e. being used for training time or early retirement). Depending on the situation of the employee and the individual life plan, the actual impact on increased participation in continuing education may therefore differ. With increasing age, it is even to be expected that the option of leaving work will become more attractive. A sustained increase in participation in continuing education and training in enterprises cannot therefore be predicted if this instrument is used.

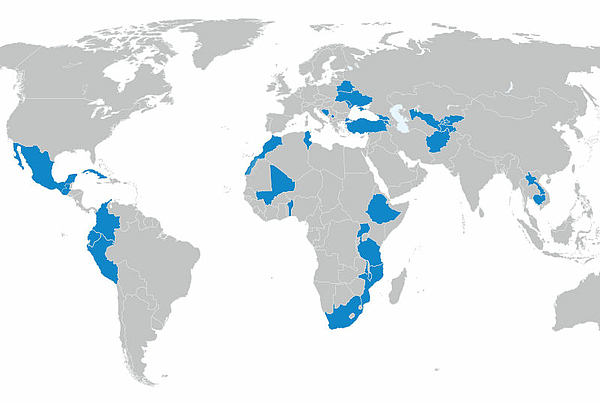

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map