Education is indispensable for a country’s development and for the improvement of living conditions of the people. Especially in South Africa, after a long colonial period and apartheid, poverty still dominates. Although it is true that more money was put into education, however, only to a very small extent in Adult Education. The number of illiterates is still high, vocational skills must be developed and, not least, the injuries caused by the apartheid system must be healed. Farrell Hunter calls for the development of new forms of learning and adoption of elements from Popular Education. The author has worked in adult education in South Africa for nearly 20 years. He is currently employed as programme manager/deputy director of the South African office of DVV International.

“Take one step back (past) to take two steps forward (from present to future)”

African Proverb

Historically, in South Africa community Adult Education or adult learning had some of its roots in basic literacy and numeracy. Much of this learning was provided in the early 1960’s for “illiterate” mine workers. This was coupled with non-formal (or informal) learning as part of the struggle for democracy within the civic movement, gender and student activism including South African Council of Sport (SACOS) – the non-racial sports movement. Notably, labour and community education was embarked upon via the black workers movement as part of the broader struggle of disenfranchised citizens fighting against the Apartheid-Capitalism system that oppressed millions of South Africans.

The shift from Apartheid to the current democratic order in 1994 has seen spaces opening up for citizens and many organizations to begin to assert their rights for social justice and to advance the social transformation agenda. Whilst one accepts, after fifteen years of democracy, advances have been made in certain areas of social life, there are many indications that in reality – social and economic trans formation and justice still eludes most South Africans – the rights of citizens on the ballot paper and in the constitution does not always translate into realities for all. As a result of the slow pace of transformation, millions of South Africans continue to live in poverty despite the rapid acquisition of wealth by a small minority. The 2009 South African Survey reveals that large percentages of people in many of the municipal regions of the country live in “relative” or “extreme” poverty – noting that South Africa’s Gini Coefficient index shows it to have the biggest gap between rich and poor compared to any other country.

There is a view that prevails that despite processes like the Truth and Recon ciliation Commission (TRC) that dealt with the traumatic experiences of victims of apartheid and tried to get disclosures by the perpetrators of “crimes against humanity” it failed to address the central question – How do we heal? The TRC had undoubtedly gone some way in dealing with its objective, yet the deep wounds of the past remain with us as a nation. This appears to be one of the reasons that rather than finding ways to identify and confront the deep seated issues that spill over from our past, we have mostly plastered over them or ignored them. Therefore some practitioners working in community development see the need for interven tions that address healing as crucial element of transformation.

South Africa is often described by eternal optimists as a country of great possibili ties, being hailed internationally for having shifted from a state of institutionalized oppression to a democratic order via a negotiated settlement. However, as a result of the nature of the oppression imposed on the country’s urban and rural working class communities subjected to hundreds of years of colonialism, followed by Apartheid using a brutal form of capitalist exploitation, one should not be surprised at the exist ence of a deeply divided, violent and multi-wounded society. Social conditions that prevail in working class communities, often with unemployment as a major contribut ing factor, include poverty (or “poverties” in the broader view – beyond the economic – see Max Neef’s Wheel of Human Needs), substance abuse, violent crime, abuse of women and children and overcrowded living conditions among others.

Many adult learning practitioners and those involved in community development in the country believe that adult learning should play a role in assisting communities to engage in the processes of transformation. This in essence should address social cohesion that will counter the negative effects of our painful history. The various strategies involving community adult learning by civil society education activists include, in the main, working for social justice and transformation, thereby paying particular attention to the challenging conditions that marginalized communities face in the present South African context.

This makes conventional approaches to education and Adult Education limited by its somewhat narrow concern for formal qualifications (certification) of learners that allows for progression towards formal skills development and to fit into the mainstream economy. Community colleges and more modest community learning centres however endeavour to offer a wider “menu” of learning opportunities to learners. Some community learning programmes have also begun to address the divisions and wounds of our history that are either masked, ignored or paid little attention to in the upper class environments or more lavish spaces occupied or fre quented by the more affluent sections of society. The Community Healing Network (CHN) in Cape Town, as one example, concentrates on creating safe spaces for healing and creating an enabling environment for social cohesion to flourish.

This historical sweep attempts to illuminate the need for adult learning with social transformation as one of its key objectives to address challenging conditions. Today, Community Adult Education takes on various forms, precisely to relate to the context as experienced by the participants or is understood by the organization facilitating the learning. Generally, Community Adult Education tries to straddle a wide range of need – providing formal education skills in basic or further education, trying to capacitate community members to improve their quality of life, the ability to par ticipate in democratic processes including bringing about social transformation.

For us in South Africa, to be relevant means addressing the challenging social and economic conditions that prevail as a result of our colonial histories.

Manifestation against violence

Source: DVV International South Africa

It is generally throught that education can and must be used as a vehicle for change and growth of countries and, accordingly, South Africa has consistently spent a significant portion of its budget on education and skills development. Since democracy, spending on education often topped 20 % of the annual budget expenditure and currently exceeds 18 %. Annually several billion Rand are spent on skills development.

Adult basic education however has been given scant attention, receiving around 1 % of the education budget despite the number of illiterates and functionally illiter ate adults – pegged at about 75 % of the number of children in schools. The state has established training authorities (Sector Education Training Authorities – SETAs) covering more than twenty various broad economic/job sectors to address skills development for youth and adults but these have not measured up to the call for a “skills revolution”. A more recent effort in the area of literacy is the government’s Mass Literacy Campaign that has begun to address the hugely neglected Adult Basic Education and Training (ABET) sector.

Results of a REFLECT training

Source: DVV International South Africa

Post Apartheid education was reconfigured to make education more accessible to all and to improve the quality of education under a unified education system. Addressing skills develop ment, on the other hand, was meant to increase the skills of the population to serve the economy in the belief that it would in turn address the issues of unemployment and poverty. However, the economy has not been able, in any consist ent way, to provide jobs for the large number of unemployed people. In fact, during the ten years following democracy in 1994, unemploy ment figures have more than doubled, to a conservative estimate of over 4 million people.

As indicated above, this poses huge challenges to development and transformation efforts.

Community education colleges offer adult basic education including Adult Ba sic Education and Training (ABET) in the formal/conventional modes of learning towards a general education, but many also offer a range of skills courses that in clude information technology, career guidance, study and writing skills for students as well as agricultural and other livelihoods skills. Then there are also courses on democracy and human rights, gender and domestic violence, social and economic rights and advocacy. The matter of HIV/AIDS as a major health and social issue for South Africa is often central to the work of many adult learning organizations as well as other community development organizations.

Unfortunately, often the profit motive and commodification of education excludes real efforts towards the transformation agenda being weaved into the curriculum, although in some cases a common over-arching theme for community adult learning organizations is making human rights and democracy real for ordinary people.

The writing of Amartya Sen (1999) has shed new light on education for real freedom. The notion of equal opportunity being enough for change has been chal lenged and the need to understand its limitations, raising the tasks of expanding and creating opportunity has been put firmly on the agenda. Gramscian thoughts on organizing for people’s power, whilst dormant over the last decade, has reap peared as relevant and a necessary element for transformation.

Information about domestic abuse

Source: DVV International South Africa

Much has been written about the predominant focus on the more formal Adult Edu cation and skills training courses on offer in South Africa but we are witnessing the re-immergence of popular Adult Education approaches as mentioned above. These address some of the learning needs and struggles of communities and individuals that resemble the non-formal forms of learning that was part of the struggle for social and economic justice during Apartheid.

As described by Liam Kane (2005), the fundamental concept of popular educa tion is its commitment in favour of “the popular classes” in their effort to “….over come oppression and injustice…”

Popular education has also found favour with peoples’ organizations in counties in Latin America and elsewhere where similar social conditions prevail as in the case of South Africa where, for example, the chasm between the haves and have-nots is stark and the slow pace of change on the part of governments calls for popular action with a learning component.

Similar popular organizations sometimes in the form of/or part of social move ments exist in countries like Brazil as in South Africa dealing with issues such as the lack of land and housing for the poor. Therefore the landless peoples’ struggles through collective and participatory campaigns for economic and social rights for shack dwellers and their demand for treatment as full citizens in South Africa saw the establishment of the movement called Abahlali Base Mjondolo. This movement is part of the Poor Peoples’ Alliance and the leadership uses forms of popular education to educate shack dwellers of their rights to housing.

Source: DVV International South Africa

Participatory popular education organizations in Adult Education in South Africa that use Freirian methods to deal with community adult learning, with literacy as a component, include the South African REFLECT Network (SARN) and the Inter national Grail, using their Training for Transformation (TfT) programmes whose “thinking and practice is grounded in communities realities”. Through these and other approaches, animators and learners as social activists critically examine the local conditions of their communities and take action to address these.

After several years of existence, SARN has taken root and has grown in several provinces in South Africa. The three time UNESCO award winning approach to adult learning, REFLECT, is finding fertile soil with former unlikely participants. These groups have found that conventional approaches do not help them to immediately reflect and address their social and economic challenges. Organizations and even a few “converts” in government departments that work in the more conventional Adult Education or community development approaches, appear open to exploring how REFLECT and other forms of popular Adult Education can make their work more effective – whether in rural, urban or peri-urban settings.

Reports show that SARN has been effective in training facilitators and establish ing dozen of learning circles in communities that have effectively, in a myriad of ways, helped to change their living conditions, socially and economically and mainstreamed HIV/AIDS into their work.

Also, at a provincial level, the South African NGO Coalition (SANGOCO) – Western Cape through its activities and the programmes of the member organi zations are beginning to explore how popular education can be integrated and employed as they engage in broader issues of health, gender, disability and other sectors. This is seen as a possibility to strengthen the efforts of NGOs and CBOs as they work at various levels and when they engage with government.

The work of Community Healing Network (CHN) believes,

“….that multiply-wounded societies run the risk of becoming societies with inter-generational traumas….. where large population groups are traumatized, the trauma is transferred to the next generation. Working with the multiple wound phenomenon means accepting that the wounds are collective as well as personal.”

The point of departure is the concept that healing is a collective challenge based on the recognition that my pain, your pain, the other person’s pain, are similar. Community healing is the epitome of this understanding and to collectively heal ourselves we need to undergo a cultural change.

Having looked at some of the challenges that face South Africa and the possibilities that exist, it needs to be said that after trying conventional approaches to address the obstacles to transformation, we need to consider our options with different lenses.

It is true that formal education and skills development can and does play a role, however, dependant on improvements and openness to rethinking the purposes of education and notions of skills development, these are important learning op portunities for those wanting to access those conventional options.

What is also necessary to begin to accept is that conventional forms of learning have not in any significant way benefited or advanced the position of marginal communities in ways required and do not address their diverse development needs.

Government, education role-players and development agencies need to view their policies, practices and resourcing differently if they are indeed serious about effectively and more speedily transforming South African society in the positive ways that are often documented but not implemented. An important aspect would be to recognize and accept the role of popular and alternative forms of learning or at least not be opposed to their role.

REFLECT training

Source: DVV International South Africa

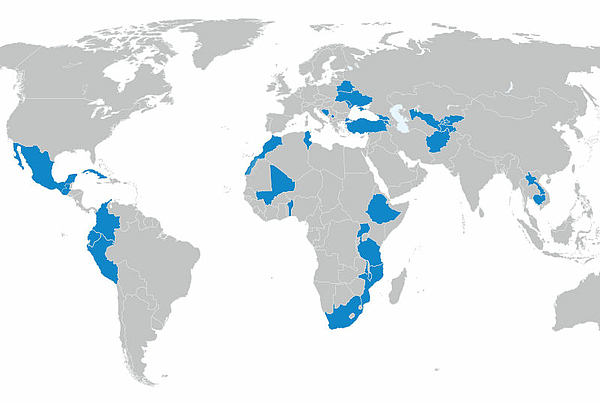

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map