Marina Silva, an indigenous Brazilian from the poorest family background, has made it: Through participation in the National Adult Education Programme, she became literate and successfully completed her studies. In 2002 she became Minister for the Environment and currently she works as a Senator. Her story can give courage to others, even if not every participant in literacy campaigns will achieve a university degree, in any case, adult education can help to improve their living conditions. Dr. Ahmed is Senior Adviser at the Institute of Educational Development, BracUniversity. He was at Belém as a UNESCO resource person.

Marina Silva, Brazilian Senator and former Environment Minister, illiterate until age 16, worked as a housemaid to support herself through adult education course and university.

Belém, Brazil. This provincial capital on the Amazon in the north-eastern state of Para was the host to the Sixth World Conference on Adult Education (CONFINTEA VI), 1- 4 December.

At the opening of the conference, Senator Maria Marina Silva, an indigenous Brazilian from the western state of Acre, one of 11 children in a family of rubber tappers, and illiterate until 16, told the emblematic and moving story of her struggle to overcome the curse of illiteracy and poverty.

Having lost her mother at 14, trapped in a life of deep poverty and a frequent victim of malaria and hepatitis, Marina decided that the only way to escape from a life of endless misery and despair was to become a nun. But she found she could not be a nun unless she was literate.

Marina traveled to the provincial capital of Rio Branco and enrolled in a course of Mobral, the national Adult Education programme. With fierce determination, working as a housemaid to support herself, Marina completed secondary education equivalency. She went on to the Federal University of Acre, and at 26, graduated with a degree in history.

Marina became an organizer of rubber plantation workers and an activist in supporting the rights of the indigenous people and conserving the fast disappearing Amazon rain forests – the target of national and multi-national industrial farmers and loggers. She was elected a state deputy in 1992, and later, in 1995, she became the youngest senator in Brazil at age 37.

With President Lula’s victory in Brazil, Marina became the Minister of Environment in 2002. Even in an era of blossoming democracy, Marina’s stand on the protection of the rain forests and the rights of the people of the Amazon was too much for the business and farming interests of Brazil. Marina Silva resigned from the Cabinet in 2008. She remains a senator and an icon among environmental activists.

Tall, thin, and youthful at 51, her voice tinged with a fighting edge, Marina’s story was both inspiring and symbolic of the hard struggle of the poor who are also deprived of literacy. It also showed the challenges that have to be faced in literacy and Adult Education programmes. Of some 3,000 children, contemporaries of Marina in Seringal Bagacao, her village with 320 famailies of plantation workers, Marina was the only one who persisted in the Adult Education course to go on to the university.

Every decade or so since the first international conference was held in 1949 in the Danish city of Elsinore, government representatives and others committed to promote Adult Education have been meeting to take stock and attempt to chart the course ahead. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was a keynote speaker in the last one held in Hamburg in 1997. State Minister of Primary and Mss Education, M. Motahar Hussain, came this time.

The world has changed radically in the last six decades; so have the ideas and expectations about education, learning and adult literacy. Meeting learning needs of youth and adults, complementing formal education provisions, is now recognised as critical for personal development and society’s progress and a matter of human right and dignity. International agreements such as the Millennium Development Goals and Education for All, as well as national constitutions, support this position.

Brazilian educator Paulo Freire famously said literacy is about reading the “world,” not the “word.” Ironically, the prominence given to literacy has led to launching of quick-fix campaigns and “movements,” though the proponents argue that it has to be designed as the first step to continuing, non-formal and Lifelong Learning.

Marina Silva

Source: Ueslei Marcelino/AP

The outcome of these campaigns is mostly not much more than a mere passing acquaintance with the alphabet or symbolic signing of one’s name. This is very far removed from Freire’s concept of reading the world, development of critical consciousness, use of knowledge and information to transform one’s life and engagement in further learning.

During the last Awami League regime, a literacy programme known as the Total Literacy Movement (TLM) was started in 1997 with the goal of making 18 million people literate in five years. In 2000, it was declared that the adult literacy rate had reached 65 percent from an estimated 40 percent. The successor BNP regime continued the programme, stood by the announced statistics, but did not claim any further progress. Corruption and lack of results led to closure of the programme in 2003.

Education Watch, an independent research group, conducted a national sample assessment of literacy skills in 2002, using recognized research techniques. It was found that 41 percent of the 15+ population had literacy and numeracy at a rudimentary level (less than functional), and only 20 percent had skills that could be regarded as functionally useful in their own life.

This state of affairs is not unique to Bangladesh. India’s official literacy rate is 65 percent. Brij Kothari, a professor of communication at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, carried out surveys following a methodology similar to the one used by Education Watch. He found, in samples drawn from four Hindispeaking states, only 26 percent could read a simple text of 35 words in Hindi. Another 27 percent could be regarded as “budding readers,” who could read haltingly with little comprehension. (International Review of Education, November 2008).

The simplistic, almost meaningless, measurement of literacy skills, based on self reporting (typically, the subject responding to the question if he/she can read and write a letter), usually as a part of population census every ten years, has encouraged the sloppy approach to literacy measurement.

In fact, it does not make sense to label people as either literate or illiterate, because literacy and numeracy have to be regarded as a continuum of skills, from very basic to more advanced. Literacy for a learner becomes sustainable (i. e., the learner is not at risk of relapsing back into illiteracy), and functionally useful, only when one goes some distance beyond the basic level.

UNESCO, the agency responsible for setting standards of assessment and tracking progress in literacy, routinely accepts national data reported by governments based on self-reporting. The current number of adult illiterates in the world according to UNESCO is 776 million. “The number would be at least double of this, if a reasonable measurement method and criteria are applied,” said David Archer of Action-Aid, a well-known Adult Education scholar. Archer also pointed out that several rates based on levels of skill acquired and corresponding numbers would be appropriate to represent the continuum of skills.

The participants of CONFINTEA VI recognized the conundrum faced in many countries with high levels of illiteracy. In the Belém Framework of Action adopted unanimously on December 4, they committed themselves to

“develop literacy provision that is relevant and adapted to learners’ needs and leads to functional and sustainable knowledge, skills and competence of participants empowering them to continue as lifelong learners.”

The Belém Framework also stipulated that all surveys and data collection should “recognize literacy as a continuum.” It requires that the achievement of the literacy learners would be “recognized through appropriate assessment methods and instruments.”

The newly elected government of Bangladesh, in fulfilling its election pledge, has plans to launch a literacy programme to “eliminate illiteracy” by 2014. The spirit of the pledge is admirable, but it is in danger of being reduced to a populist and meaningless tokenism, for reasons noted above. The TLM experience of the past must not be repeated.

It is essential that: a) the goals and targets for 2014 be defined in terms of bringing learners into a process of sustainable and relevant learning which will continue beyond 2014; b) an institutional structure for Lifelong Learning be developed in phases in the form of a network of multi-purpose and permanent community learning centers through local government and in partnership with community and non-governmental organizations; and c) quality and relevance of the learning programme be ensured with appropriate content and learning materials, motivated and trained teachers, and proper assessment of outcomes.

A credible programme for adult literacy placed in a Lifelong Learning framework has a good chance of attracting the Education for All “Fast Track Initiative” Fund, set up by donors to support EFA.

It is not expected that every participant in an Adult Education programme will emulate Marina and graduate from the university. However, a programme worth its name has to ensure that most acquire knowledge and competencies to improve their life chances.

Participants from the Woman Network REPEM

Source: Claudia Ferreira

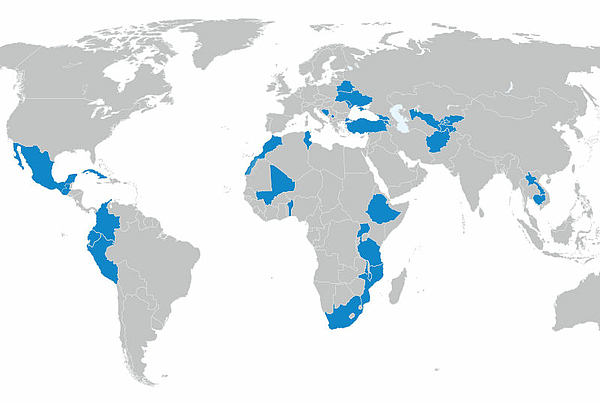

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map