Gorgui Sow

Gorgui Sow

Education specialist, Senegal

Abstract – In this article, the author presents a fundamental problem, which is the lack of interest on the part of many African governments vis-à-vis the literacy of their young adult population. This is a population where more than 50% is usually illiterate. It is not only a problem of lack of political will, but a lack of political consciousness: African leaders must be conscious of the fact that illiteracy in youth and adults is the most formidable obstacle to growth and sustainable development of African nations.

For the author, the discussion on what should happen after 2015 shows that the attention of education providers on the issue of successful learning in primary school may make adult literacy even more of a problem. For a long time to come, Africa is likely to remain one of the richest continents with the poorest people.

Illiteracy is one of the biggest challenges for Africa. First of all because it is one of the largest regions of the world burdened with the highest illiteracy rate – over 40% of the population over 15 years of age. Africa is also where the factors contributing to illiteracy are most present: the highest proportion of children who do not have access to primary education or leave school early (40%), or who have not even mastered basic skills at the end of primary school (50%), with a high risk of falling into illiteracy.

The United Nations declaration Literacy Decade (2003–2012) reaffirms the role of literacy at the heart of the fundamental human right to education. The human right has a number of key characteristics: It is inseparable from the recognition of human dignity and, therefore, it is universal in that it is acknowledged for all people irrespective of social origin, gender, race, ethnicity or age.

These principles of inseparability and universality remain empty words when the law is ineffective. Mr. Mamadou N’doye, the former Executive Secretary of the Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA), reminded us of this during the first ADEA triennial in February 2012 in Ouagadougou. The ethical obligation of States is therefore not just about formally recognising these principles but above all to create the conditions for effective literacy for all.

Africa’s rendezvous with 2015

Africa’s rendezvous with 2015The year 2015 will be a very critical rendezvous for governments and the partners of education in Africa. Two important processes will eventually meet their deadline (the agenda of Education for All – EFA, and the Millennium Development Goals – MDG). 2015 will also be the

midpoint after the last UNESCO World Conference on Adult Education (CONFINTEA VI and the Belém Framework for Action).

In the same year, Africa will also rendezvous with a large number of political and budgetary deficits in literacy for youth and adults. This situation is the result of several factors, some of which are endogenous (economic hardship, political and institutional instability, civil war, etc.), and others which are exogenous (marginalization of EFA Goal 4 of the Dakar Framework for Action in favour of universal primary education).

In February 2012 the first ADEA Triennial in Ouagadougou attracted over 1,000 education stakeholders from the national and international level. I had the privilege to ask a question to the panel of three heads of state – Burkina Faso, Niger and Ivory Coast – invited to this event.

My question was: “Excellencies, as you so well reaffirm, education is a fundamental right, and if you consider that the basic education of citizens in your countries is a priority for your governments, why then do you all put so little money into literacy for youth and adults?” (Less than 1% of the education budget.)

Jeff Koinange, the famous Kenyan journalist enlisted by the ADEA to animate this unusual panel, had a smile on his lips and seemed surprised to see the three heads of state look at each other and writhe with embarrassed laughter in the face of the applause from an audience that apparently shared my concerns.

We remained hungry for an answer even after the responses given successively by our honourable guests.

Indeed, the three countries mentioned above are among those with the most illiterate youth and adults in West Africa. We see the slowest rate of political struggle against illiteracy in those countries, and as a result they will not even reach EFA Goal 4 in 2020 (that of reducing the adult illiteracy rate by 50% in 2015).

Ivory Coast has a population of nearly 22 million, of whom nearly 50% are illiterate (or nearly 11 million). Even if the government was capable of bringing literacy to 500,000 adults per year through projects funded by the Ivorian state and by donors, it would mean that the Ivory Coast would not reach Goal 4 until 2023.

Regarding Niger and Burkina Faso: despite the bold policies of the last decade to fight against illiteracy, the two countries will not meet Goal 4 before 2025, unless these states triple the resources allocated to this sector by 2015.

Prioritisation of literacy for youth and adults in the context of poverty and socio-political crisis goes beyond political will, but it is a constituent part of the political consciousness of African leaders. A democratic and egalitarian Africa will be created only with well educated African citizens, aware of their rights and responsibilities. In the words of Professor Cheikh Anta Diop: “The African citizen should be armed to the teeth with science” in order to make Africa a sovereign and developed continent.

Unfortunately the scarce resources allocated to the literacy sector show the willingness of African governments to relegate literacy for youth and adults to the background.

During the last two decades, NGOs and some African governments have done a lot of useful things in the sub-sector LNFE (Literacy and Non-Formal Education). Take for example Burkina Faso, where the foundations have been put in place to promote LNFE. In Mali, YELEMBOU, a large popular movement, was launched to eradicate illiteracy among youth and adults. In Senegal, the so called “Faire-faire” policy (working through partners) was able to mobilise all the civil society stakeholders, the communities and the state to reduce the illiteracy rate by 5% each year.

It is unfortunate that very little has been documented in an attractive way or otherwise used as examples. This inability to sell LNFE products to the communities and to the education partners makes the financing of quality literacy increasingly uncertain. The noted lack of transparency in the implementation of certain LNFE projects and the lack of certification doesn’t exactly help either.

In Africa, even if we have managed to make early childhood development a priority for the Decade of Education in Africa (launched by the African Union), we have so far not been able to do the same for LNFE. The African Union is a showcase of the realities and priorities of member countries. We hope that the efforts made in this field by ADEA, UNESCO, the African platform for literacy, the African Network Campaign on Education For All (ANCEFA), Pan African Association for Literacy and Adult Education (PAALAE), African Women’s Development and Communication Network (FEMNET), African Reflect Network (PAMOJA) and many other stakeholders regarding the right to education will not be in vain.

In its advocacy strategy to make Education For All a priority in the agenda of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) beyond 2015, ANCEFA, in partnership with national coalitions and partners like ADEA, UNESCO, Save the Children, Plan (Promoting child rights to end child poverty), OSISA (Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa) and ActionAid, managed to pass a declaration at the last Conference of Ministers of Education of the African Union (COMEDAF) in Abuja asking African governments to make education inclusive and LNFE a priority for 2015 and beyond.

Many governments do not prioritise literacy for youth and adults. This makes it even more difficult to get adequate funding from education donors. Multiple and often uncoordinated interventions by NGOs are like “the tree that hides the forest”, making state financing even more insignificant.

The wake-up call will be very difficult in 2015, and after 2015 may result in an even more unjust treatment of youth and adult literacy since:

The strategic priorities of the new Global Partnership for Education (GPE) have already identified areas in which the countries of Africa, Asia and Latin America must invest in order to gain access to international funding. [For more on GPE, click here]

Governments wishing to benefit from external resources for LNFE after 2015 will have to rethink their strategies for fundraising for this sub-sector by integrating literacy programs in their development policies for early childhood, schooling of young girls or the promotion of education and employability of young people excluded from national education systems.

The African industrial and mining sector, which is boiling with billions of dollars each year, should not fear an income tax whose sole purpose is to pull the men and women who daily earn them this wealth out of poverty and ignorance. African countries have an urgent duty to fund the development of the basic technical and vocational skills of their citizens from the revenues that emanate from natural resources.

Beyond the bounds of the political consciousness of this particular time, it will be a source of pride for Africans and all activists in a free Africa!

Gorgui Sow is a psychologist by training; he worked as a researcher and trainer in the field of evaluation and monitoring of learning, the use of national languages at school. Later he became one of the most famous defenders of the right to education in Africa. Mr. Sow headed the African Network Campaign on Education for All (ANCEFA) for ten years where he organised and supported several campaigns for literacy for youth and adults with UNESCO, the Global Campaign for Education (GCE) and the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE).

POBOX 3007

Dakar Yoff

Senegal

gorgui.sow@gmail.com

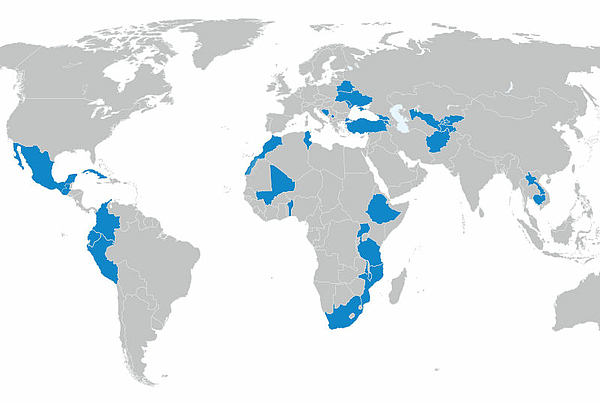

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map