From left to right:

From left to right:

Phyllis In’utu Sumbwa

University of Zambia

Wanga Weluzani Chakanika

University of Zambia

Abstract – The study “Factors Leading to Low Level Participation in Adult Literacy Programmes Among Men of Namwala District” looks at why men will not participate in adult literacy programmes.

Reasons for not participating include shyness, a feeling of being too old for any learning, or the feeling that participating in adult literacy programmes will be a sheer waste of time. The study recommends that the government should provide an infrastructure specifically for adult literacy programmes and that the providers should sensitise the community regarding the benefits of participating.

Most Southern African countries are struggling with the challenge of how to deal with growing levels of illiteracy and particularly illiterate adults. Although it is well established that Adult Education is a powerful tool for sustainable development, it is obvious that specific and deliberate policies need to be put in place for its effectiveness (Caffarella 2001). However, in most African countries, policy has been considered unimportant when combatting adult illiteracy. Take Zambia, where efforts have been made towards a policy on Adult Education since gaining independence in 1964. To date, no such policy exists. Instead Adult Learning and Education is guided by a number of different policy documents, for example“National Policy on Community Development, Educating our Future, National Youth Policy, National Agriculture Policy, National Gender Policy, National Employment and Labour Market Policy” (MoE 2008). The result is a haphazard approach in the provision of Adult Education, as there is no guiding document to the providers of such programmes.

Zambia also lacks a clear policy on non-formal education (Mumba 2000). Despite the multiplicity of providers of adult literacy programmes (which include government ministries, parastatal organisations, church organisations and Non-Governmental Organisations), there are no benchmarks, and this makes it difficult to co-ordinate and monitor the sector. Following the “World Conference on Education For All” in Jomtien in 1990, Zambia held a National Conference which stated that there was a need to reassert the political commitment to providing education as a human right. The fact that no policy still exists shows that there has been a lack of political will.

In addition, funding of adult literacy programmes in Zambia, and the world over, is usually inadequate, inconsistent and uncoordinated (Aitchison & Hassana 2009). In Zambia, Adult Education programmes are not funded as stand-alone programmes but are under the umbrella of education in general. This has been exacerbated after the shifting of adult literacy activities from the Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health, where it received more attention, to the Ministry of Education (MoE 2010). The latter, being more concerned with the education of children and youths, have so far not provided the necessary support and funding that Adult Education deserves. Funding entails a clear need for the investment in capacity development and having sufficient and well qualified professional staff to take an interest in such programmes (Aitchison & Hassana 2009). Under-funding poses a threat to the sustainability of adult literacy programmes. In 2010, most African countries spent 0.3% to 0.5% of the education budget on Adult Education. In Zambia, 0.2% of the total budgetary allocation to education was spent on Adult Education activities.

Another challenge in the provision of adult literacy programmes has to do with tailoring the programmes for women. The reason is that there are more illiterate females than males. Therefore, most programmes are designed to meet the needs of female illiterates.

Namwala is a rural district situated in the Southern Province of Zambia. It shares boundaries with four districts: Monze to the southeast, Choma to the south, Kalomo and Itezhitezhi to the northwest. It covers an area of about 10,000 square kilometres.

According to the 2002 census, the population of the district is about 83,000 (49% males, 51% females) mostly living in major settlement areas (CSO 2003).

Most of the land in the district is covered by plains and is used for the grazing of cattle (Namwala District Development Plan 2006–2010).

200 persons are included in the study. Some were selected because of their official role in adult literacy programmes (for example the District Commissioner), others were either participants or non-participants in literacy programmes.

The study identifies a number of reasons why men do not enrol in adult literacy programmes. First, it was discovered that generally, literacy levels in Namwala District are far below expectations, mainly due to a lack of commitment by the government to alleviate illiteracy. But the main problem is elsewhere. The major factors have to do with culture and tradition. Men are expected to fend and provide for their families; engaging in any adult literacy activity is not a priority. Instead, they devote most of their time to income-generating activities. As a result, even young boys are withdrawn from school at an early stage (as early as primary school) so that the older men can prepare them for adult life. Secondly, the pride of men in the district is determined by how many head of cattle a man has, number of wives a man married and the number of children one has. Therefore, men work tirelessly in an effort to acquire as many herds of cattle as possible. After that, they can marry as many women and have as many children as they desire. Acquisition and possession of the above was and is still considered as evidence of being rich.

Traditional leaders also play a role in discouraging men from attending adult literacy programmes. These leaders still hold on very strongly to archaic traditional beliefs and practices. As a result they encourage their subjects to engage in early marriages and other traditional practices which do not place priority on education or adult literacy activities. One recommendation is therefore to get traditional leaders to unlearn some of the archaic practices which may not be relevant for this generation. In its place new trends can be suggested, trends which may even bring about development in their chiefdoms. Traditional ceremonies, such as “Shimunenga” in the Maala area, are also cited as major deterrents. This ceremony is about“showing off” how many herds of cattle a man has. Men are, therefore, preoccupied with preparations for such ceremonies for most part of the year leaving no room for adult literacy programmes.

Why then, do some men still enrol in adult literacy programmes? Simply to learn how to read and write. This, they state, will open up opportunities for them, like land a job or write letters and fill out relevant documents, for example at the bank. Some participants also feel that by being literate, they will improve their farming and livestock management skills. This would lead to an improved livelihood.

The pride of an Ila man lies in how many cattle he has, after which he can marry as many women as he would like thereby commanding respect in the society and being considered wealthy. The picture shows an Ila man with his five wives.

Both basic and functional literacy are being offered in Namwala District. In basic literacy, participants appreciate the fact that they are able to read and write and even calculate simple arithmetic. Functional literacy enables them to make their environment respond to their needs.

Basic literacy

The basic literacy programmes enable adults who may or may not have had the opportunity of accessing formal education to be able to understand the problems of their immediate environment. It also sensitises participants to their rights and obligations as citizens and individuals. Kleis (1974) notes that this type of education enables participants to participate more effectively in the economic and social progress of their community. Basic literacy provides a platform for adult learners as it provides the minimum knowledge and skills which are an essential condition for attaining an adequate standard of living.

Functional literacy

Functional literacy combines reading, writing and simple arithmetic and basic vocational skills directly linked to the occupational needs of participants. The skills acquired in functional literacy classes are believed to be important for survival. Similarly, Burnet (1965) states that literacy or being literate goes beyond merely being able to read and write but being able to apply the skills acquired by such an individual to improve their lives. However, this has been viewed purely from an economic perspective. The participants are engaged in learning only to become more efficient and productive. They have no chance to impact the learning process. The type of functional literacy currently being offered simply leads to further oppression because it doesn’t offer participants the chance to develop themselves sustainably. The skills acquired are only adequate for carrying out activities required of a person by society.

Freire (1974) suggests a kind of “functional literacy” that liberates learners from the culture of silence and frees them in order to reach their full potential. The ideal, therefore, is one where learners are not treated as objects but as subjects, capable of working to change their social reality (Grabowski 1994).

In other words, such an individual is able to make the environment respond to his/her needs. A variety of skills are taught in the district, ranging from agricultural management skills to business management skills. Learners are also taught bricklaying, carpentry and joinery as well as gardening. These adult functional literacy programmes are offered to a cross section of men of various age-groups.

Although men are hard to reach, a growing trickle of male participants have been coming to – in particular – functional literacy classes.

One reason is that men view adult literacy programmes as their window of hope in improving their well-being. Participants argue that a literate person is able to improve his health, sanitation, production and even home management. In addition, the study reveals that men view adult literacy programmes as a modern way of understanding their environment and making them able to adjust to its dictates.

Almost 92% of the respondents indicate that their lives have improved after acquiring skills through the adult literacy programmes.

The study notes that a literate person is able to meet civic rights and obligations by knowing about and observing regulations, participating in group discussions and in the efforts to ensure civic improvement and voting without help. These include satisfying religious aspirations through reading sacred literature and participating in various religious activities. These ideas are also echoed in focus group discussions, where discussants state that those who are literate are able to read the Bible and acquire leadership positions in both their communities and Christian communities.

King and O’Driscoll (2002) state that as adults grow in their ability to read and write, they also acquire an understanding of their world. This understanding is key to acquiring a keener insight, more rational attitudes, and improved behaviour patterns for their own development. This is why we see a slight increase in male participation in adult literacy programmes as compared to a decade ago where adult literacy programmes were considered to be a woman’s affair only.

On the other hand, there is still a myriad of reasons why men in the Namwala District do not attend literacy classes. Notable among them is an individual’s feelings, thoughts and attitudes toward himself and to any learning activity. For many reasons, the majority of men are very difficult to attract into a structured learning environment.

Respondents clearly state that participation depends on an individual’s confidence and interest and that lack of confidence and low self esteem are key dispositional barriers to male participation in adult literacy.

The study shows that men feel shy to engage in adult literacy programmes mainly because they want to protect their ego. In addition, the physical environment, administrative and pedagogical practices of education and training do not fit their age and status in society.

Another barrier has to do with current life situations. Respondents point out that they are usually busy with other activities and they see no reason to participate in adult literacy programmes as they are expected to provide for their families.

Lack of opportunities after involvement in adult literacy programmes is also suggested as a deterrent to prospective male participants. Clear and accurate information and clear guidance to facilitate the appropriate choice of programme is suggested as being a factor which would encourage male participation. In other words, men want to know, from the initial stage, what opportunities will be opened up for them after attending adult literacy programmes.

Looking at the skill sets of facilitators, the study establishes that a variety of methods are used which are appreciated by learners. Findings show that facilitators are knowledgeable in conducting adult literacy programmes. The majority have adequate education. Usually facilitators take up that role after the community has chosen them. However, their delivery is hampered by a lack of developed infrastructure and a lack of teaching aids as well as funding.

The study investigates factors inhibiting men’s participation in adult literacy programmes. In doing so, the study also delves into the details of what motivates adult males to participate. The study finds a variety of adult literacy programmes helping people to raise their knowledge levels in managing their lives.

The study therefore makes the following recommendations:

References

Aitchison, J. and Hassana, A. (2009): The State and Development of Adult Learning and Education in Sub-Saharan Africa. UNESCO.

Burnet, M. (1965): A B C of Literacy. Paris: UNICEF.

Central Statistical Office (2003): Zambia Demographic Health Survey Education Data Survey 2002: Education and Data for Decision Making.

Lusaka: CSO.w

Chakanika, W. W. and Sumbwa, P. I. (in press): Factors Leading to Low Levels of Participation in Adult Literacy Programmes Among Men in Namwala District. Lusaka: University of Zambia.

Corridan, M. (2002): Moving from the Margins: A Study of Male Participation in Adult Literacy Education. Dublin: Adult Learning Centre.

Dale, E. (1965): Is there a substitute for reading? Newsletter, Vol. X, April 1945. Bureau of Educational Research: Ohio State University.

Freire, P. (1974): Education for critical consciousness. London: Sheed and Ward Ltd.

Giroux, H. (1989): Schooling for Democracy: Critical Pedagogy in the Modern Age. London: Routledge.

Grabowski, J. (1994): Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’. New York: Continuum.

Grain, S. et al (1988): Educational Equity and Transformation. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

King, L. and O’Driscoll, B. (2002): Gender and Learning: A Study of the Learning Styles of Women and Men in the Implications for further Education and Training. Shannon Curriculum Development Centre.

Kleis, R. (1974): Programme of Studies in Non-Formal Education: Study Team Reports. Washington D.C.: Institute for International Studies in Education.

McGivney (2004): Men Earn, Women Learn: Bridging the Gender Divide in Education and Training. Leicester: NIACE.

Ministry of Education (2010): Report on the Status of Adult Literacy in Zambia: Policy on Adult Education.

Mumba, E. (2000): Curriculum for Basic Non-Formal Education. Ministry of Community Development and Social Services.

O’Connor, M. (2007): Gender in Irish Education. Dublin: Department of Education and Science.

Owens, T. (2000): Men on the Move: A Study of Barriers to Male Participation in Education and Training Initiatives. Dublin: Aontas. Available at http://bit. ly/1ebU8gK

UNESCO and UNDP (1976): The Experimental World Literacy Programme: A Critical Assessment. Paris: UNESCO.

Phyllis In’utu Sumbwa is from Zambia and is 34 years old. She first got exposed to the field of Adult Education in the year 2005 when she started her certificate programme in Adult Education. She immediately proceeded to her Diploma in Adult Education, a bachelor’s degree and a Master’s degree in the same field in the years 2007, 2009 and 2013 respectively. Since 2010, she has been a Staff Development Fellow (SDF) in the School of Education, Department of Adult Education and Extension Studies of the University of Zambia. As SDF, she conducted a number of Adult Education tutorials, for example in Research Method in Adult Education, Participatory Approaches to Development and Evaluation of Adult Education programmes, just to mention a few. Her specific area of interest in Adult Education is that of Adult Literacy.

University of Zambia, School of Education

Department of Adult Education and Extension Studies

P. O. Box 32379

Lusaka, Zambia

phsumbwa@yahoo.com

Wanga Weluzani Chakanika is a senior lecturer in the Department of Adult Education and Extension Studies at the University of Zambia. Currently, he is actively involved in teaching and supervising literacy work at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. He has also researched and published articles related to Adult Education. From 1995 to 1999, he was the National Chairperson of the Adult Education Association of Zambia. During this time, the Association concentrated on, among other things, undertaking research in various fields of Adult Education.

University of Zambia, School of Education

Department of Adult Education and Extension Studies

P. O. Box 32379

Lusaka, Zambia

chakanikaitis@yahoo.co.uk

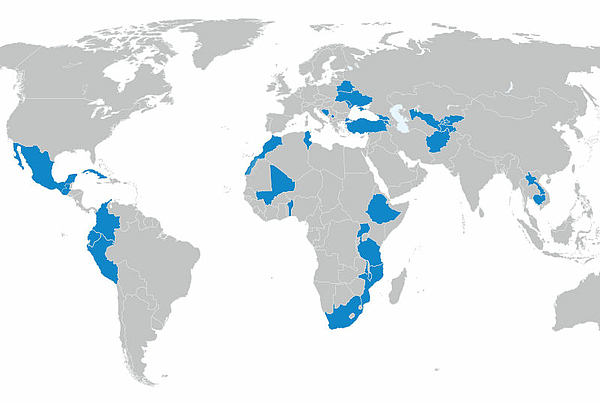

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map