Astrid von Kotze

Astrid von Kotze

Popular Education Programme

South Africa

Abstract – The communities of Vrygrond in the greater Cape Town municipal area are engulfed in unemployment, poverty, conflict and violence. The Popular Education Programme has run a variety of courses over the last three years aimed at building community leadership for affecting unity and collective action for transformation. While there is some evidence of personal development, larger structural changes are necessary if hunger and violence are to be eradicated, thus resulting in a thriving community.

PEP participant

Xolela’s fourth grandchild, brother to a year-old sister, has just been born. His mother is barely 20 years old and his father is yet again behind bars for drug-dealing. They live with Xolela and her other daughter and 2 children in a 3-room shack constructed out of cardboard, corrugated iron and plastic in Overcome Heights, one of the 5 ‘camps’ (shack settlements) in the greater Vrygrond area.

Xolela is HIV positive, a housing activist and is running a women’s support group. After demonstrating a keen interest in education, together with three others from Vrygrond she now attends Adult Education classes at the university, studying towards a Diploma in Adult Education. She struggles to prioritise her engagements and often runs from one meeting and action group to another.

Xolela is one of the inception members of the Popular Education Programme (PEP) in Vrygrond, now in its fourth year, and she has recently initiated a new course to be run for members of the women’s support group. While exemplary, she is just one of many extremely resilient women in the area who suggests “if we could get something like this [popular education] and empower them [community members] and give them a taste of real education it would change their lives.”

Vrygrond (Free Ground) and its environs is located near the False Bay sea board in the greater Cape Town municipal area. The history of Vrygrond is one of constant change in response to the political pressures imposed by Apartheid legislation and engineering on the one hand, and stories of increasing intergenerational rural-urban migration, unemployment, homelessness, and intra-African migration on the other.

Vrygrond is one of the oldest settlements in the Western Cape, where self-reliant families pursued a simple way of life over many decades. The first wave of residents settled on the beach dunes around 1942 and were characterized as “trek” fishermen. The Expropriation Act passed in this period removed many families from the neighbouring area of Retreat to the growing population of Vrygrond. The next wave in the 1970s was a result of Apartheid social engineering when many households were uprooted from District Six in Cape Town and forced into large blocks of flats in Lavender Hill. The next expansion produced Sea Winds in the eighties. In the last two decades smaller housing schemes were created through the RDP (Reconstruction and Development Programme) housing thrust initiated by the new democratic government.

Meanwhile, five large shanty communities Village Heights, Hillview, Militar y Heights, Overcome Heights and Cuba Heights grew to over 6000 people by the late nineties and today the number of residents is estimated at 35,000. Schools and clinics can barely cope with the increasing number of residents and unemployment is approaching 70%. Vrygrond is a Babel of many languages; the streets are populated by children and youth spilling out of their homes and competing for public space. There is music from across Africa pumping particularly out of hairdressing businesses in shipping containers and informal pubs. The sound of church bells is interspersed with mullana calling. The wind blows litter into rain puddles and the pollution is testimony to limited service delivery from the city.

In 2011 the Popular Education Programme was formed by community development and Adult Education activists. It builds on traditions of ‘People’s Education’ embedded in the South African anti-apartheid struggles of the nineteen-eighties, the philosophy of Paulo Freire as practiced in ‘Training for Transformation’ and popular culture. Its purpose is to contribute to progressive social and political change by building grassroots leadership. Unlike formal education, popular education begins with the daily realities of participants. There is a strong focus on issues of power, inequality and injustice as par ticipants in popular education ‘schools’ explore who makes the decisions that affect us all and ask: in whose interests are those decisions?

Popular education claims to achieve some important things; in particular:

One par ticipant echoed these aims when she said: “To me these sessions are valuable in terms of learning because each and ever y day I attend a session, I gain more knowledge through group discussions and these debates help me to express my own views. Most discussions are about our communities, like what role we play to make our community develop, free from hunger, pover ty, free from crime, with improved healthcare.”

PEP in Vrygrond

The choice of sites for popular education work was not random: the whole Vrygrond/Lavender Hill area is extremely volatile, as incidents of personal and community issues related to social and economic exclusion and oppression are very high. In the three months towards the end of 2013 alone, over 30 people were killed in the area in drug-related gang war fare. Children are especially vulnerable as they grow up with a sense that violence is normal and recruitment of boys as young as ten into gangs is common. Furthermore, one of the PEP facilitators lives in the area and is actively engaged in community organisations on a daily basis. This ensures continuity, support and follow-up.

In the last three years, PEP has run ten ‘popular education schools’ (PES) and three ‘popular education development’ (PED) courses in Vrygrond, working with diverse groups of residents and grassroots organisations. While ‘direct’ participants in those courses numbered approximately 150, the ripple effects on household members and community groups extends far beyond these participants. As one participant commented: “I’d go home every week and tell my daughters and my whole family ‘We learned about this and that’; I was so excited. I inspired other people to want to know more; I was passionate about it. My enthusiasm lead another group to want to do the course, from singing the praises of what

we were learning.”

A PES comprises twelve 2-hour sessions, run once a week in whatever space can be found – ranging from metal containers, to individuals’ garages or community centre rooms. The PES curriculum focuses on community development, social issues, crime, human rights, basic research skills and an introduction to campaigning. Classes are highly participatory and (English) literacy is not required.

Parenting session at iThemba Pre-School.

The PES 2 focused on ‘how to prepare, organise and run

a campaign’ and the group completed its programme by organising and running an event on ‘child abuse’ for parents of pre-school children. Par ticipants made posters, designed the programme, formulated a brief for the guestspeaker and each took on the role of facilitator for the 50 parents who attended. Course par ticipants commented that “what we learned here we implemented – not just learning something and it goes nowhere.”

In 2012, PEP offered a PES 3 course for ex-PES 1 and 2 participants. This ran over 5 months (27 sessions) and was entitled ‘Power, Advocacy and Living Well’. The main focus was on food and food security/sovereignty. Many of the participants changed their nutrition habits and moved towards greater awareness of food production and healthy consumption in the course of PES 3. Having learned “to ask questions, not just to accept and to do things practically” they took their insights further, remarking “how the decisions we make or are forced on us has a negative af fect on the survival of mother nature and how our mindset changes can make life better for all and the earth.”

A 16-week course for the volunteers at a local women’s organisation that looks af ter under-five year olds in the mornings, feeds approximately 150 children at lunchtime, and runs an after-school programme in the af ternoons, happened on Fridays. The course focussed on ‘neglect’ experienced on a large scale by the children. Participants analysed the underlying social, economic and political causes of neglect and abuse and examined these in the light of a changing world.

Participants then practiced a variety of facilitation processes aimed at improving communication and cooperation, with a particular emphasis on power, gender and culture.

The women developed personal and interpersonal communication skills; they articulated clearly how relationships with peers, family and children changed for the better, and they were able to explain gender and power – how these impact everything in their world. Participants described how as a result of the courses they communicate dif ferently with their children (“I don’t shout at them any more but tr y and explain”) and relate to colleagues more effectively.

Understanding the causes of violence and substance abuse has helped them to try less confrontational strategies. They are more able to take on public issues and speak with clarity and confidence, and this has motivated them to continue learning, and in turn, becoming role models for the youth in their families: “If this course was star ted five years ago, I think it would have made changes in our community,

so they wouldn’t have to bring in the army to deal with gang violence. People in the community could do things for themselves. If more parents were equipped with this kind of knowledge they would be able to help their kids more by being ahead of the game.”

Capacitar exercises.

Overcome Heights is the largest of the five camps in Vr ygrond, comprising approximately 3500 shack dwellers. Representatives from the nine sections in the camp attended a PED held at a church venue in the camp and thus avoided the dangers of a long walk. Despite the ongoing violence in the area most members completed the practical work, including weekly report back meetings for all residents and house visits. An important characteristic of this PED thrust was building on proactive positive actions.

Martha Cabrera has pointed out how “Trauma and pain afflict not only individuals. When they become widespread and ongoing they affect entire communities and even the country as a whole. The implications are serious for people’s health, the resilience of the country’s social fabric, the success of development schemes, and the hope of future generations.” While positive actions helped participants to regain their sense of agency, the trauma and stress of living and working under the socio-economic, environmental and political conditions of the area were beginning to tell.

PEP responded by initiating a ver y well-attended PES in ‘Body Literacy’ to which all PEP par ticipants were invited. The course included practical Tai Chi and Capacitar exercises and promoted intensive reflection. Par ticipants ar ticulated strong levels of personal development, such as improving empathy and the capacity to help others in moments and situations of trauma: “I have discovered the inner workings of my body and mind. It has taught me to respect myself and other human beings per se”; “I relaxed and don’t get pains anymore”; “I’ve discovered it helps me personally as I regard myself easily aggravated and moody. So, personally, I find it to be something as a pacifier at times”. They also suggested how they could use their new-found strengths and skills of relaxation “to assist in training and implementing practices like this in the community, as it will certainly help reducing the levels of crime”.

Each year, PEP has built on the preceding year by extending the number and range of people par ticipating in PES or PED. It became clear that the demands far outstripped the provision. The answer has been to train trainers. In 2013 the first such course was of fered, and residents such as Xolela was one of the participants. PEP also established connections between her and three others from the area with the university to enable them to continue their quest for education and skills development.

The desire to learn is, in itself, a positive phenomenon as most participants have negative memories of schooling and persistent experiences of various put-downs and violence have lead to a low sense of self-worth: Now, “I’ve learnt that ever ybody is equal and that I should not be intimidated by others who put themselves on a throne and make me feel less important because of financial category…” and “This knowledge can be used practically from the subject of nutrition to that subject of social action and political systems. It is transformative knowledge that can change the way communities think and behave. It helped create passion in me to become active in being part of change for the good of my own life as well as that of others.” And: “What I found exciting is the teaching on how we can build a better society for all. I found that if we can work together as a team we can achieve a lot of goals. I found that fighting crime in a society needs the whole society to come together and unite against it, then we have a better society.”

PEP par ticipants are of ten key initiators of community action such as public demonstrations against drugs and gangs. They challenge local politicians at meetings and participate in housing activism. They have made repeated attempts to form cooperatives and contributed to food gardens to alleviate daily food insecurity. They have organised youth leadership training and women’s support groups – but broader systemic and structural changes are needed if Vrygrond is to become a better place.

Hunger and violence stand out as significant obstacles: food needs contribute significantly to people’s ability to sustain par ticipation. Par ticipants who work as volunteers in local community-based organisations have to take on any paid work they can in order to meet bills. Gang-related violence directly impacts our programmes in terms of absenteeism and cancellation of sessions as participants are at risk of being shot at or caught in cross-fire on the way to and from sessions, par ticularly in the early evening.

References

Cabrera, M. (n.d.): Living and sur viving in a multiply wounded countr y. Available at http://bit.ly/1ofDHCM

Freire, P. (1970): Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Hope, A. and Timmel, S. (1999): Training for Transformation Vol 1–4. Kleinmond: Tf T Institute.

Astrid von Kotze is a community education and development practitioner working in the Popular Education Programme in working class communities in/around Cape Town. She has done extensive work developing par ticipator y teaching/learning materials with a social-justice purpose. Until 2009, she was Professor of Adult Education and Community Development at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. She is an extraordinary professor in The Division for Lifelong Learning at the University of the Western Cape.

Contact

9 Scott Rd

Observatory

7925 Cape Town

South Africa

astridvonkotze@gmail.com

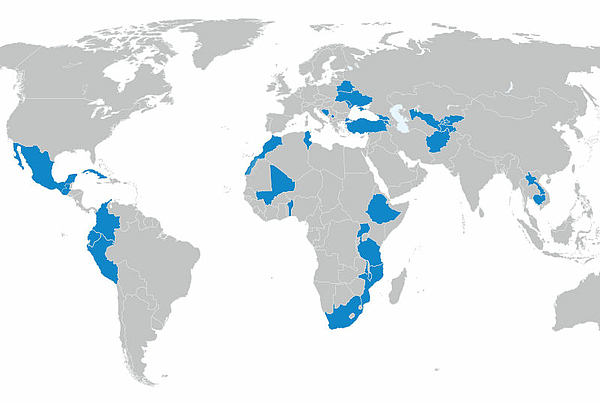

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map