Jan Fredriksson

Jan Fredriksson

DVV International

Germany

July, 2016, Achacachi, Bolivia. The environmental educator Edwin Alvarado Terrazas is on the eastern shore of Lake Titicaca, 96 km from La Paz and at an altitude of 3854m. He is teaching a class at the Avichaca Centre for Alternative Education. Edwin and the villagers have gathered in a courtyard. The environmental educator just filled water into a glass and a bucket. While pointing at the bucket he says: “This part is salt water. It is in the seas and oceans. If we were to drink salt water every day, we would do damage to our kidneys.” Then he lifts up the glass, with an amount of water many times smaller than that found in the bucket, and warns: “From this fresh water, only one small part is available to us.” To demonstrate the value of the fresh water available, he fills a syringe with less than a millilitre and approaches the participants: “This is the water we humans know about. All the groundwater we know about is here!” Edwin has just shared the most important information and has also caught the attention of the people. Now he can continue, explaining what can happen if the body of a cow or a used battery comes into contact with the water all human life depends on.

When one asks Edwin Alvarado Terrazas about the environmental situation in Bolivia, he leaves one with no doubt as to the problems his country is facing. According to Edwin, it is due in large part to the massive use of industrial products by a society that still has neither adequate infrastructure nor the environmental education necessary to handle these products safely. He is especially critical of the fact that they are sold to citizens without them being aware of the environmental implications of their purchase: “The ‘modern world’ seeks them out in order to accommodate products and services, but not to indicate the risk of, for example, the in adequate final disposal of the batteries of cell phones.”

There are three main issues that are troubling Edwin: toxic waste, agrochemicals and plastic waste. Over recent years, a veritable flood of electrical appliances, mobile phones and other electronic products have arrived in the homes of Bolivians – all these products contain toxic substances, but there is almost no infrastructure for their secure storage or their safe recycling: “We don’t have a planned, structured, technological way to deal with these wastes. It is obvious to me that there is an initial failure regarding the subject Environmental Responsibility of Enterprises and in some cases of the state. For example, a very important phone company in Bolivia reports that it signed an agreement with a recycling company to remove used cell batteries. I followed this for two years and the company never left Spain to come to our country. With measures like this you can’t take the first step to success.”

© ARD Alpha/Bayerischer Rundfunk

In agriculture, pesticides and other potentially harmful substances are used even though many farmers and workers are not qualified to handle these products safely: “The street vendors sell them to poor people who have no training and don’t get information.” Edwin warns that these sellers tend to take advantage of the ignorance of their customers: ‘It’s the best!’ ‘It’s stronger; it’s better!’ ‘More, more, you really have to put it on!’ That is what is heard in the streets.”

Finally, Edwin affirms that, with the arrival of a lifestyle oriented toward rapid consumption, the use of plastic packaging in the everyday life of Bolivians has increased exponentially: “The ‘fast life’ makes us big consumers of packaging, bags, and it’s all plastic! Packed lunch for a family of five persons: 5 plastic bags for soup, five bags for the main dish, the salad aside, another bag, peppers and other meat, another bag, spicy llajua [sauce based on tomato and red peppers], another bag, the refreshments, another bag ... and multiply that. It's frightening.”

There is no lack of work for an environmental educator in Bolivia – but where to start? Edwin’s approach is pragmatic and realistic, trying to concentrate on the possible: He can’t exert much pressure on businesses nor accelerate political or congressional action. But he can tell people about their dependence on nature through a short demonstration with a bucket, a glass and a syringe. It can help the Andean people to rediscover their traditional respect for Pacha Mama – Mother Earth – and the realisation that the damage done to it also hurts the community. It is useful to revive the close relationship between man and earth: For a farmer, to take the corpse of a cow away from a sewer so as not to contaminate water is ust merely an extra duty after a long day – the protection of Pacha Mama is a matter of honour and pride.

However, it is essential to connect this notion of pride with practical instruction, says Edwin: “In the end, each one of them have cell phones much more modern than mine.” Consequently, what really counts is knowing how to act once the cell phone no longer works. Many people are willing to do their part, but don’t know how. They lack the most basic information about the negative effects appliances, agrochemicals or plastic products may have if they come in contact with available fresh water reserves. According to Edwin, the task of environmental educators is to disseminate practical knowledge like this: “Through the medium of education, we inform them about the risks involved in buying these products on the street, the categories of risk for the products – which now have colour classifications according to their degree of toxicity – of the risks to health, the economy and production (agri-pastoral) and of the possibility of combating pests and to fertilise soil with natural recipes.”

Edwin tries to transmit to his students all the knowledge necessary for them to protect Pacha Mama on their own, Environmental educator Edwin Alvarado Terrazas demonstrates how scarce drinking water is (Courtesy of ARD Alpha/Bayerischer Rundfunk). without any outside support. He emphasises that this is necessary because there is still a lack of infrastructure to treat toxic waste and plastic adequately: “From nine major cities and 339 municipalities, only three have suitable facilities for the treatment of special waste. One city – just recently – began collecting electronic waste. All of them have copy-cat campaigns to ‘collect’ this waste, but the result is a hoax. An NGO announced one of these campaigns to collect batteries – inappropriately calling it recycling – in the town of Copacabana, nearby the magnificent Titicaca. All the students participated, with support from the mayor, and once all the mountains of batteries were collected, they buried them near the lake! It’s a time bomb.” He confirms that there is only “one municipality that, in the scope of its powers, tries to regulate these issues and create infrastructure and systems for the recovery of hazardous waste through campaigns.”

Environmental educator Edwin Alvarado Terrazas demonstrates how scarce drinking water is. © ARD Alpha/Bayerischer Rundfunk

Where there is no official and definitive solution, a temporary solution must be found on the private level. Edwin believes that it is best not to mobilise or gather too much waste in order to avoid problems and massive risks: “In 336 municipalities it’s only possible to teach, for example, transitional home confinement of polluting waste, with rudimentary domestic methods: Place your batteries in properly covered PET con-tainers, keep them out of reach of children. And when the container is full, store it in some home-made concrete structure.”

© ARD Alpha/Bayerischer Rundfunk

Despite all his criticism, Edwin does not have a completely pessimistic view of the environmental situation in Bolivia. He sees tangible progress on plastic waste: “The changes in Bolivia have been important in the last 15 years. Previously no one even imagined the possibility of separating waste at its source, because the companies contracted by the municipality for collection and treatment mixed all waste together. The day will come when municipal contracts contemplate differentiated collection and utilisation of waste.

Villagers learn to understand the fundamental connection between their own behaviour and the ecological situation in their area. © ARD Alpha/Bayerischer Rundfunk

‘Uka jach’a uru jutaskiw!’ say the Aymara: ‘That great day is coming!’ Our capital, La Paz, just approved its first contract for solid waste management with a company that must collect waste differentially and deliver it to a processing plant composting organic waste – which is already operating on a small scale – and a plastics reprocessing factory (recycled plastic material used for example to make fences, floors and car bodies) which is also in early-stage operation.”

In addition to progress on a practical level, Edwin sees important advances in the field of environmental education: “There are strong entities working to enhance and restore cultural values.” Edwin highlights three broadcasters committed to the welfare of the indigenous and peasant population: Radio San Gabriel, that calls itself “the voice of the Aymara people”; ACLO, the Jesuit radio network, which claims on its website that “through our advocacy of social, economic and productive development, educative communication – in harmony with the environment – we seek to achieve a good life.”

Finally, Edwin mentions the radio channel of the Jaihuayco Centre for Continuing Education (CEPJA), which has programmes in the Quechua language. “In these cultural areas there is an understanding, for example, that water is the blood of Mother Earth. In this sense, I think it will be possible – in a short time, in the medium term – to connect with contemporary issues, because it is about saving the life of Mother Earth.”

Jan Fredriksson is the DVV International senior desk officer for information and communication. Previously, he has been working as a broadcasting and print journalist for many years.

Contact

fredriksson@dvv-international.de

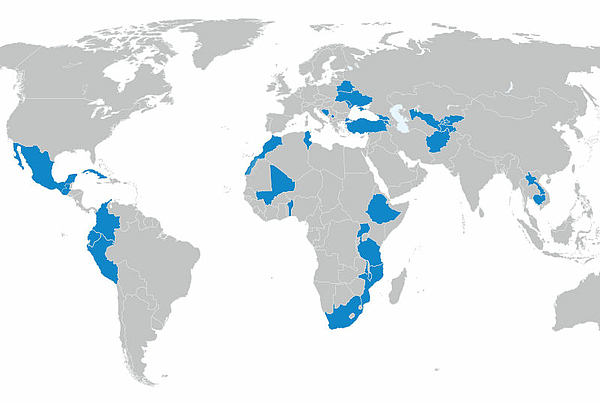

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map